(Article by Peter C. Gøtzsche republished from BrownStone.org)

In 2013, I estimated that our prescription drugs are the third leading cause of death after heart disease and cancer,1 and in 2015, that psychiatric drugs alone are also the third leading cause of death.2 However, in the US, it is commonly stated that our drugs are “only” the fourth leading cause of death.3,4 This estimate was derived from a 1998 meta-analysis of 39 US studies where monitors recorded all adverse drug reactions that occurred while the patients were in hospital, or which were the reason for hospital admission.5

This methodology clearly underestimates drug deaths. Most people who are killed by their drugs die outside hospitals, and the time people spent in hospitals was only 11 days on average in the meta-analysis.5 Moreover, the meta-analysis only included patients who died from drugs that were properly prescribed, not those who died as a result of errors in drug administration, noncompliance, overdose, or drug abuse, and not deaths where the adverse drug reaction was only possible.5

Many people die because of errors, e.g. simultaneous use of contraindicated drugs, and many possible drug deaths are real. Moreover, most of the included studies are very old, the median publication year being 1973, and drug deaths have increased dramatically over the last 50 years. As an example, 37,309 drug deaths were reported to the FDA in 2006 and 123,927 ten years later, which is 3.3 times as many.6

In hospital records and coroners’ reports, deaths linked to prescription drugs are often considered to be from natural or unknown causes. This misconception is particularly common for deaths caused by psychiatric drugs.2,7 Even when young patients with schizophrenia suddenly drop dead, it is called a natural death. But it is not natural to die young and it is well known that neuroleptics can cause lethal heart arrhythmias.

Many people die from the drugs they take without raising any suspicion that it could be an adverse drug effect. Depression drugs kill many people, mainly among the elderly, because they can cause orthostatic hypotension, sedation, confusion, and dizziness. The drugs double the risk of falls and hip fractures in a dose-dependent manner,8,9 and within one year after a hip fracture, about one-fifth of the patients will have died. As elderly people often fall anyway, it is not possible to know if such deaths are drug deaths.

Another example of unrecognised drug deaths is provided by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They have killed hundreds of thousands of people,1 mainly through heart attacks and bleeding stomach ulcers, but these deaths are unlikely to be coded as adverse drug reactions, as such deaths also occur in patients who do not take the drugs.

The 1998 US meta-analysis estimated that 106,000 patients die every year in hospital because of adverse drug effects (a 0.32% death rate).5 A carefully done Norwegian study examined 732 deaths that occurred in a two-year period ending in 1995 at a department of internal medicine, and it found that there were 9.5 drug deaths per 1,000 patients (a 1% death rate).10 This is a much more reliable estimate, as drug deaths have increased markedly. If we apply this estimate to the US, we get 315,000 annual drug deaths in hospitals. A review of four newer studies, from 2008 to 2011, estimated that there were over 400,000 drug deaths in US hospitals.11

Drug usage is now so common that newborns in 2019 could be expected to take prescription drugs for roughly half their lives in the US.12 Moreover, polypharmacy has been increasing.12

How Many People Are Killed by Psychiatric Drugs?

If we want to estimate the death toll of psychiatric drugs, the most reliable evidence we have are the placebo-controlled randomised trials. But we need to consider their limitations.

First, they usually run for only a few weeks even though most patients take the drugs for many years.13,14

Second, polypharmacy is common in psychiatry, and this increases the risk of dying. As an example, the Danish Board of Health has warned that adding a benzodiazepine to a neuroleptic increases mortality by 50-65%.15

Third, half of all deaths are missing in published trial reports.16 For dementia, published data show that for every 100 people treated with a newer neuroleptic for ten weeks, one patient is killed.17 This is an extremely high death rate for a drug, but FDA data on the same trials show it is twice as high, namely two patients killed per 100 after ten weeks.18 And if we extend the observation period, the death toll becomes even higher. A Finnish study of 70,718 community-dwellers newly diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease reported that neuroleptics kill 4-5 people per 100 annually compared to patients who were not treated.19

Fourth, the design of psychiatric drug trials is biased. In almost all cases, patients were already in treatment before they entered the trial,2,7 and some of those randomised to placebo will therefore experience withdrawal effects that will increase their risk of dying, e.g. because of akathisia. It is not possible to use the placebo-controlled trials in schizophrenia to estimate the effect of neuroleptics on mortality because of the drug withdrawal design. The suicide rate in these unethical trials was 2-5 times higher than the norm.20,21 One in every 145 patients who entered the trials of risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and sertindole died, but none of these deaths were mentioned in the scientific literature, and the FDA didn’t require them to be mentioned.

Fifth, events after the trial is stopped are ignored. In Pfizer’s trials of sertraline in adults, the risk ratio for suicides and suicide attempts was 0.52 when the follow-up was only 24 hours, but 1.47 when the follow-up was 30 days, i.e. an increase in suicidal events.22 And when researchers reanalysed the FDA trial data on depression drugs and included harms occurring during followup, they found that the drugs double the number of suicides in adults compared to placebo.23,24

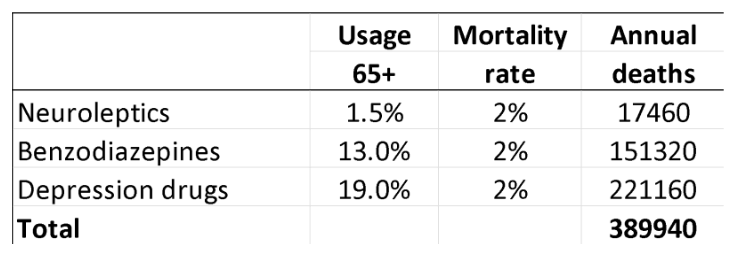

In 2013, I estimated that, in people aged 65 and above, neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, or similar, and depression drugs kill 209,000 people annually in the United States.2 I used rather conservative estimates, however, and usage data from Denmark, which are far lower than those in the US. I have therefore updated the analysis based on US usage data, again focusing on older age groups.

For neuroleptics, I used the estimate of 2% mortality from the FDA data.18

For benzodiazepines and similar drugs, a matched cohort study showed that the drugs doubled the death rate, although the average age of the patients was only 55.25 The excess death rate was about 1% per year. In another large, matched cohort study, the appendix to the study report shows that hypnotics quadrupled the death rate (hazard ratio 4.5).26 These authors estimated that sleeping pills kill between 320,000 and 507,000 Americans every year.26 A reasonable estimate of the annual death rate would therefore be 2%.

For SSRIs, a UK cohort study of 60,746 depressed patients older than 65 showed that they led to falls and that the drugs kill 3.6% of patients treated for one year.27 The study was done very well, e.g. the patients were their own control in one of the analyses, which is a good way to remove the effect of confounders. But the death rate is surprisingly high.

Another cohort study, of 136,293 American postmenopausal women (age 50-79) participating in the Women’s Health Initiative study, found that depression drugs were associated with a 32% increase in all-cause mortality after adjustment for confounding factors, which corresponded to 0.5% of women killed by SSRIs when treated for one year.28 The death rate was very likely underestimated. The authors warned that their results should be interpreted with great caution, as the way exposure to antidepressant drugs was ascertained carried a high risk of misclassification, which would make it more difficult to find an increase in mortality. Further, the patients were much younger than in the UK study, and the death rate increased markedly with age and was 1.4% for those aged 70-79. Finally, the exposed and unexposed women were different for many important risk factors for early death, whereas the people in the UK cohort were their own control.

For these reasons, I decided to use the average of the two estimates, a 2% annual death rate.

These are my results for the US for these three drug groups for people at least 65 years of age (58.2 million; usage is in outpatients only):29-32

A limitation in these estimates is that you can only die once, and many people receive polypharmacy. It is not clear how we should adjust for this. In the UK cohort study of depressed patients, 9% also took neuroleptics, and 24% took hypnotics/anxiolytics.27

On the other hand, the data on death rates come from studies where many patients were also on several psychiatric drugs in the comparison group, so this is not likely to be a major limitation considering also that polypharmacy increases mortality beyond what the individual drugs cause.

Statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention list these four top causes of death:33

Heart disease: 695,547

Cancer: 605,213

Covid-19: 416,893

Accidents: 224,935

Covid-19 deaths are rapidly declining, and many such deaths are not caused by the virus but merely occurred in people who tested positive for it because the WHO advised that all deaths in people who tested positive should be called Covid deaths.

Young people have a much smaller death risk than the elderly, as they rarely fall and break their hip, which is why I have focused on the elderly. I have tried to be conservative. My estimate misses many drug deaths in those younger than 65 years; it only included three classes of psychiatric drugs; and it did not include hospital deaths.

I therefore do not doubt that psychiatric drugs are the third leading cause of death after heart disease and cancer.

Read more at: BrownStone.org

Please contact us for more information.